This is an all-out, no holds barred, full-fledged takedown of the downright treasonous among us. We’re no longer hearing a political divide in America today, but a death knell. Democrats don’t have a different vision for American, but a death wish. There is no such thing as political discourse or debate with Democrats—political projectionists who demonize and damn their political dissenters for the damnable and destructive things that they themselves are doing. The notion that Democrats are still just a political party proposing high ideals is preposterous. Instead, they are fifth columnists perpetrating high treason! If ever successful in their hostile takeover of our representative republic, not only will the future of our country be forfeited, but also the future of our children. And just think, it’s these same tyrannical and treasonous Democrats who demand that we be scorned and squared off against as the enemies of our constitutional republic.

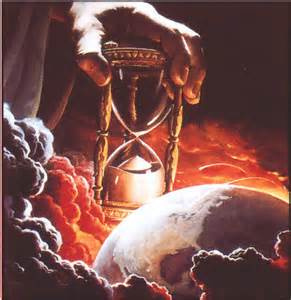

It is truly unconscionable to me that so many Americans have been hoodwinked by Democrats into believing that supporting Democrats’ demolition of our nation is the way to rebuild it into a socialist utopia, which will be but a part of an emerging peaceful and prosperous globalist-controlled paradisiacal planet. Yet, my Bible does teach me that an end-time world will be swept away in delusion, because of its rejection and hatred of the truth, and that a beastly world power will arise in the last days that will create, not heaven on earth, but the greatest hell on earth this fallen world has ever known. It looks to me like we’re well on our way to it, and nothing, no angel in Heaven, no devil in Hell, and no man on earth, can stop or prevent it.

The evidence that Democrats may well prove to be the pawns in the hands of Divine Providence that are used to bring about the Biblically predicted and preordained end-time scenario is mounting. Despite their barefaced anti-Americanism, proven in a plethora of different ways, and them being monstrously and manifestly antichrist and antisemitic, millions of deluded Americans are still marching hypnotically to their tune and being seduced by their siren song, totally unaware that they, like moths to the flame, are rushing to their own destruction, as well as the destruction of their own children and country.

Truly, there is no other explanation for any American to any longer support a political party that is feverishly working for the downfall of our nation than demonic deception. Again, as the Bible clearly teaches, the end-time world will be possessed by the spirit of antichrist, which will result in a final all-out war on the people of God, both His chosen people, Israel and the Jews, and His elect people, the church and Christians. What other explanation is there for today’s intolerant Democrats, who, despite feigning to be the world’s foremost fighters against intolerance, are so intolerant toward Jews and Bible-believing Christians, as to declare open season on them alone? Why is it that Israel and Bible-believing Christianity are the only two targets in Democrats’ crosshairs? This, my friend, is no coincidence, but I fear the invisible hand of Divine Providence, pushing our world, which is increasingly being possessed with the spirit of Antichrist, right up to the threshold, of the great tribulation of the Biblically predicted perilous times of the last days.

Wake up church! While our fellow countrymen, as well as our fellow man, will sleepwalk into the night of the coming dark days, there is, as the Bible teaches us, no reason for us to do so (1 Thessalonians 5:4-6). We need to be awake to all that is going on, so that we can be soberly watching and seriously praying (1 Peter 4:7). Let us be like the children of Issachar, men and women who understand the times and know what we should do, not like the rest of the world, which will sleepwalk right up to the time that sudden destruction comes upon it (1 Chronicles 12:32; 1 Thessalonians 5:2-3).