English Translations

The first translation of any part of the Bible into English was done by Bede. It is known as the “Venerable Bede.” Bede was an English monk, as well as a skilled linguist and translator, who translated the Gospel of John from Latin to Anglo-Saxon in 735 AD.

No existing copies of Bede’s translation of John’s Gospel are still in existence. There is, however, a beautifully illuminated manuscript of an eighth century English translation of all four Gospels into English on display today in London’s British Museum. It is known as the Lindisfarne Gospels and is the oldest existing copy of the four Gospels in the English language in all the world. According to a note added at the end of the manuscript, less than a century after it was finished, the manuscript was the work of a skilled artist monk called Eadfrith, who was the Bishop of the Holy Island of Lindisfarne, which is located off the northeast coast of England.

It was not until the fourteenth century, more than 500 years after the initial translations of the Gospels into English in the eighth century, that someone dared to take up the tremendous task of translating the whole Bible into English. This daring soul was named John Wycliffe. Although Wycliffe’s translation is primarily attributed to him, his translation of the Old Testament had to be finished by friends after his death, which occurred sometime around 1384 AD. It was not until the fourteenth century, more than 500 years after the initial translations of the Gospels into English in the eighth century, that someone dared to take up the tremendous task of translating the whole Bible into English. This daring soul was named John Wycliffe. Although Wycliffe’s translation is primarily attributed to him, his translation of the Old Testament had to be finished by friends after his death, which occurred sometime around 1384 AD.

Today’s Wycliffe Bible Translators, a Christian missionary organization dedicated to translating the Bible into languages of unreached people groups, gets its name from John Wycliffe. Although the Bible is by far the most translated book in the world, there are still thousands of languages into which the Bible has not been translated. Even more tragic is the fact that it is estimated that 1.7 billion people in our world today have never even heard the name of “Jesus,” the one “name under heaven given among men, whereby we must be saved.”1 Truly, there is an ever-increasing urgency for Christians today to get God’s Word to the unreached people of this fallen planet, a planet that is fast running out of time.

John Wycliffe is undoubtedly one of the greatest figures in all of Christian history. He was born in Yorkshire, England around 1330 AD. Educated at Oxford, Wycliffe stayed on to become Oxford’s most brilliant theologian, as well as the greatest preacher and debater of his time. He was called by his contemporaries, “the Flower of Oxford.”

In his study of the Scripture, Wycliffe came to see that the teachings of the Catholic Church were at variance with the teachings of the Bible. The church had forsaken the Word of God for its traditions and usurped the authority of Scripture in the lives of the people. Therefore, Wycliffe demanded that the Bible be restored to the people and that its authority once again be established in the church. To this end, he set out to translate the Bible into English so that English-speaking people could read the Bible for themselves.

Needless to say, John Wycliffe’s demand for an English translation of the Bible, which would free the English-speaking people of the world from having their faith dictated to them by the papacy, incurred no little hostility from the Roman Catholic Church, which in many ways sought to imprison and punish him for his egregious “heresy.” Had it not been for Wycliffe’s powerful friend John of Gaunt, the Duke of Lancaster, who was the real power behind the throne of his senile father, King Edward III of England, Wycliffe’s career as a reformer of the church would have proven short-lived.

John Wycliffe’s demand that the Bible be restored to the people and that its authority once again be established in the church was the turning point in doctrinal history. Up until Wycliffe, tradition had been placed alongside Scripture and given equal authority. The Bible had been kept from the common people and turned into the exclusive property of the church, which alone was deemed competent to interpret its teachings. John Wycliffe’s demand that the Bible be restored to the people and that its authority once again be established in the church was the turning point in doctrinal history. Up until Wycliffe, tradition had been placed alongside Scripture and given equal authority. The Bible had been kept from the common people and turned into the exclusive property of the church, which alone was deemed competent to interpret its teachings.

As hard as it is for us to believe, most English-speaking people in John Wycliffe’s day had never seen a Bible. If they had, they couldn’t have read it, because it was only available in Latin. This led Wycliffe to adopt as his life’s goal the translation of the Bible into English. This great theme of his life is summed up in his famous statement: “The sacred Scriptures be the property of the people, and one which no party should be allowed to wrest from them.”

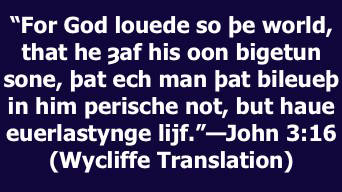

In defiance of the church, which had actually, not to mention unbelievably, outlawed the reading of the Scriptures in the people’s native tongue, John Wycliffe set out to translate the Bible into English. His translation was taken from the Latin Vulgate, not from the original languages. He finished his translation of the New Testament around 1380. His friends finished the Old Testament translation sometime after Wycliffe’s death around 1384. Afterward, for the first time in history, the English-speaking people of our world had a Bible to read in their own language.

Despite the fact that Wycliffe’s translation of the Bible provided the English-speaking people of our world with their own Bible to read, a single copy of Wycliffe’s Bible could take as long as a whole year to produce. We must remember that Wycliffe’s English translation of the Bible preceded the time of the printing press. Therefore, it had to be copied by hand. In addition, it was only the wealthy who could afford the high cost of a copy of Wycliffe’s Bible. Despite the fact that Wycliffe’s translation of the Bible provided the English-speaking people of our world with their own Bible to read, a single copy of Wycliffe’s Bible could take as long as a whole year to produce. We must remember that Wycliffe’s English translation of the Bible preceded the time of the printing press. Therefore, it had to be copied by hand. In addition, it was only the wealthy who could afford the high cost of a copy of Wycliffe’s Bible.

Undeterred by how hard it was to get one’s hands on a copy of Wycliffe’s Bible, as well as by the high cost of a copy, English paupers would join together to give a load of hay for the use of a few favorite chapters for a single day. Sometimes they even pooled their pennies to buy a small copied passage to share among themselves. To think of the desperate measures the poor were willing to employ just to get their hands on a small passage of Scripture for a single day certainly speaks to the shame of modern-day Americans, who live their daily lives largely indifferent to the Word of God. Though it is readily available and most affordable, few people in our country today ever bother to pick up a Bible or to peer into it.

The fact that there are 170 handwritten copies of Wycliffe’s English translation of the Bible still in existence today, proves the great number of people who worked at copying the Scripture, as well as the great number who desired to own the forbidden treasure.

To help spread the Word of God and to distribute the Scriptures, Wycliffe established a group of men called “Bible Men.” Wycliffe’s enemies called them “Lollards,” which means “mumblers.” These men went everywhere, not only to read the Bible to people, since most of the people were illiterate, but to preach and teach the Bible to the people as well.

Some time after the death of Wycliffe, in the early 1400s, persecution drove the Lollards underground. For the first time in the history of England, the stake was decreed against the disciples of Christ and preachers of the Gospel. Many Lollards were burned at the stake with a copy of Wycliffe’s Bible tied around their neck. Others were branded on the cheek with a hot iron, some with “L” for Lollard, and others with an “H” for heretic. So many Lollards were imprisoned during this time of persecution that the prisons in England became known as “Lollard Towers.”

One of the things Wycliffe most violently attacked in the Catholic Church was indulgences, the church’s selling of forgiveness and of passes to get out of purgatory. Wycliffe wrote of the Pope and his collectors, the friars: “They draw out of our land poor men’s livelihood, and many thousand marks, by the year, of King’s money, for sacraments and spiritual things, that is cursed heresy of simony, and maketh all Christendom assent and maintain this heresy.”

Before his 60th birthday, John Wycliffe suffered the first of three strokes. The friars rejoiced at the news and rushed to Wycliffe’s bedside believing he would repent of the “evil” he had done to them and the church, by violently attacking the Catholic Church’s practice of indulgences. Gathered about the supposed dying man’s bedside, the friars said to him, “You have death on your lips, be touched by your faults, and retract in our presence all that you have said to our injury.”

Motioning to his attendant to set him up in the bed, Wycliffe responded in a clear and strong voice, “I shall not die, but live; and again declare the evil deeds of the friars.” Astonished and embarrassed, the monks all hurried from the room.

In his old age, expelled from Oxford and forsaken by his former protector, John of Gaunt, Wycliffe was summoned before the highest ecclesiastical tribunal in the kingdom. Here, at the Blackfriars Synod in 1382, Wycliffe would again be called on to recant. However, when the 47 bishops, monks and doctors of religion took their seats in judgment of Wycliffe, a powerful earthquake suddenly shook the city. Wycliffe immediately declared it “a judgment of God” and thereafter referred to the Synod as the “Earthquake Council.”

Although expected at long last to recant when called upon to do so by the gathered bishops, monks, and doctors at the Blackfriars Synod, Wycliffe defiantly responded to their demand for his recantation. He daringly declared: “With whom, think you, are you contending? with an old man on the brink of the grave? No! with Truth—Truth which is stronger than you, and will overcome you.” Wycliffe then walked out of the assembly, without any of his adversaries attempting to stop him. Although expected at long last to recant when called upon to do so by the gathered bishops, monks, and doctors at the Blackfriars Synod, Wycliffe defiantly responded to their demand for his recantation. He daringly declared: “With whom, think you, are you contending? with an old man on the brink of the grave? No! with Truth—Truth which is stronger than you, and will overcome you.” Wycliffe then walked out of the assembly, without any of his adversaries attempting to stop him.

Before his death, Wycliffe was summoned to appear before the papal tribunal in Rome. There he was to answer to the pope for the charge of heresy leveled against him. He would have obeyed the summons had it not been for a second stroke, which made his journey to Rome impossible. He did respond, however, in a letter. Among other things, he wrote the following, “No faithful man ought to follow either the pope himself or any [other so-called] holy men, but in such as [they have] followed the Lord Jesus Christ.”

During a worship service in his own church in Lutterworth on December 29, 1384, Wycliffe suffered his third stroke. He died two days later. Over forty years after his death, the Council of Constance decreed Wycliffe’s bones be dug up, publicly burned, and the ashes thrown into the Swift River.

Afterward, this most fitting tribute to Wycliffe was penned: “This brook hath conveyed his ashes into Avon, Avon to Severn, Severn to the narrow seas, they into the main ocean. And thus the ashes of Wycliffe are the emblem of his doctrine, which now is dispersed all over the world.” Afterward, this most fitting tribute to Wycliffe was penned: “This brook hath conveyed his ashes into Avon, Avon to Severn, Severn to the narrow seas, they into the main ocean. And thus the ashes of Wycliffe are the emblem of his doctrine, which now is dispersed all over the world.”

John Wycliffe has been called the “Morning Star of the Reformation.” Without Wycliffe there may have never been a Protestant Reformation or an English translation of the Bible. In my humble opinion, with the lone exception of the Apostle Paul, John Wycliffe is the most important figure in all of Christian History!

Almost 70 years after the death of John Wycliffe an immeasurably significant event took place. In 1450, John Gutenberg of Mainz, Germany, invented the printing press. No longer would copies of the sacred text have to be produced by hand, but could be mass produced on the printing press. The first major work to be produced on Gutenberg’s Press was the Bible. It was the Latin translation, which was printed by Gutenberg in 1456.

In 1516, the first Greek New Testament was printed. It was the work of a man named Erasmus. Thanks to Erasmus, scholars, for the first time in history, had access to the New Testament in its original language. One of these scholars was an Englishman named William Tyndale, whose chief ambition in life was to provide the people of England with an English translation of the New Testament based on the original Greek. In 1516, the first Greek New Testament was printed. It was the work of a man named Erasmus. Thanks to Erasmus, scholars, for the first time in history, had access to the New Testament in its original language. One of these scholars was an Englishman named William Tyndale, whose chief ambition in life was to provide the people of England with an English translation of the New Testament based on the original Greek.

William Tyndale was born in England around 1492. Like John Wycliffe, he too was educated at Oxford. The church became upset with Tyndale when he began to teach what John Wycliffe had taught; namely, that every man should be able to read the Bible for himself.

In condemnation of Tyndale’s perceived heresy, one Catholic priest said, “We had better be without God’s Laws than the Pope’s.” In response, Tyndale made this famous reply, “I defy the Pope and all his laws, and if God spare me, I will one day make the boy that drives the plow in England to know more of the Scripture than the Pope himself.”

William Tyndale was the first person to translate the New Testament from Greek to English. Remember, Wycliffe’s English translation of the New Testament was from the Latin Vulgate. Although Tyndale began his translation in England, he had to flee to Germany to complete it, because of fierce opposition to his work in his native land. After a year of great stress in Germany, Tyndale was able to complete his translation in 1525.

Tyndale’s translation of the New Testament was not only the first to be translated from Greek to English, but it was also the first printed translation of the New Testament into English. Unlike Wycliffe, who could only turn out one handwritten copy of his translation every few months, Tyndale could turn out hundreds of copies of his translation in a single day. In early 1526, the first copies of Tyndale’s New Testament were smuggled into England.

When copies of Tyndale’s English translation of the New Testament began appearing all over England, British troops were assigned to the ports to confiscate them and bring them to Saint Paul’s Cross in London, where they were burned by the thousands. Tyndale, however, just printed thousands more. He even started printing a small edition that could be put on cargo ships and smuggled into England in boxes, bales of cloth, wooden barrels, and sacks of grain and flour.

Cuthbert Tonstal, the Bishop of London, enlisted Augustine Pakington, one of England’s leading merchants, to buy every copy of Tyndale’s New Testament he could find in Europe. Tonstal told Pakington he was willing to pay any price for the New Testaments, in hopes of acquiring them all so that he could destroy every last one of them. Unbeknownst to Tonstal, Pakington was a friend of Tyndale’s. Together, Tyndale and Pakington plotted to have Tonstal buy Tyndale’s New Testaments at exorbitant prices so that Tyndale would have more money than ever to print more New Testaments. Tyndale ended up laughing all the way to the bank and England was flooded with Tyndale’s New Testaments!

As he had promised, Tyndale’s translation of the New Testament was definitely for the “ploughboy.” For instance, instead of the word “penance” Tyndale used the word “repentance” and instead of the word “charity” Tyndale used the word “love.” Many biblical words familiar to us today were coined by William Tyndale. Some examples are: “peacemaker,” “passover,” “scapegoat,” and “longsuffering.” This is why Tyndale has been called “the Father of the English Bible.”

After translating the New Testament into English from the original Greek, Tyndale turned his attention to translating the Old Testament into English from Hebrew. In 1535, however, he was betrayed, arrested, and thrown into prison near Brussels in Belgium. For two years he rotted away, wrapping thin rags around him to keep warm. He wrote a letter from prison requesting a “warmer cap” and “a warmer coat also.” His letter went on to say: “My overcoat is worn out; my shirts are also worn out…And I ask to be allowed to have a lamp in the evening…But most of all, I beg and beseech…that I might kindly be permitted to have the Hebrew Bible, Hebrew grammar, and Hebrew dictionary.” Even in the horrid conditions of his imprisonment, Tyndale was determined to finish his translation of the Old Testament. Unfortunately, he only managed to live long enough to translate the Books of Moses, the Books of History, and some of the prophets. After translating the New Testament into English from the original Greek, Tyndale turned his attention to translating the Old Testament into English from Hebrew. In 1535, however, he was betrayed, arrested, and thrown into prison near Brussels in Belgium. For two years he rotted away, wrapping thin rags around him to keep warm. He wrote a letter from prison requesting a “warmer cap” and “a warmer coat also.” His letter went on to say: “My overcoat is worn out; my shirts are also worn out…And I ask to be allowed to have a lamp in the evening…But most of all, I beg and beseech…that I might kindly be permitted to have the Hebrew Bible, Hebrew grammar, and Hebrew dictionary.” Even in the horrid conditions of his imprisonment, Tyndale was determined to finish his translation of the Old Testament. Unfortunately, he only managed to live long enough to translate the Books of Moses, the Books of History, and some of the prophets.

On Friday, October 6, 1536, William Tyndale was brought from prison to the public square to be executed for the crime of heresy. He was tied to a stake and strangled to death by the hangman. Afterward, his body was burned to ashes. His last words, spoken in a piecing loud voice were, “Lord, open the king of England’s eyes.”

The completion of the Old Testament from Hebrew to English, as well as the completion of the English translation of the whole Bible from the original languages, was finally accomplished by Miles Coverdale. Coverdale was not the scholar Tyndale was, but he was a man, like Tyndale, whose great ambition in life was to provide the people of England with an English translation of the Bible from the original languages. Coverdale’s translation was the first complete Bible printed in English.

Once Coverdale’s translation came off the press and began to be circulated in 1535, other English translations began to appear as well. Matthews Bible was issued in 1537. Taverner’s Bible was issued in 1539. Also issued in 1539 was the Great Bible, which was edited by Miles Coverdale and the first English translation of the Bible ever authorized to be read in the churches. Every church in England was furnished with a copy of the Great Bible.

Interestingly, many English pastors opposed the Great Bible, complaining that their congregations were reading the Bible rather than listening to their sermons. I suspect many a modern-day pastor would lodge the same complaint if their Sunday morning pews were filled with more Bible readers. Unfortunately, most contemporary churchgoers are Biblical illiterates, content to get their understanding of the Christian Faith from their pastor’s sermons rather than their personal study of the Scripture.

Of all the sixteenth century English translations of the Bible, the most popular by far was the 1560 Geneva Bible. It was called the Geneva Bible because it was printed in Geneva, Switzerland, an important center of the Protestant Reformation, being the city of both John Calvin and John Knox. Its popularity was due in no small part to its legible type, convenient size, and accompanying commentary. It quickly became the Bible of the English household.

The Bishops’ Bible, issued in 1568, was an English translation of the Bible called for by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Matthew Parker. It was intended to counter the Calvinism of the Geneva Bible, which was found in the Geneva Bible’s notes, not in the translation itself. The Bishops’ Bible got its name from the fact that it was translated by the Bishops of the Church of England. Upon its completion, it replaced the Great Bible as the authorized translation to be read in all English churches.

The Roman Catholic Reims-Douai Bible was issued in 1610. It was an English translation of the Bible from the Latin Vulgate intended to defend Roman Catholicism against the onslaught of the Protestant Reformation. It was called the Reims-Douai Bible because it was translated by translators from the English College of Douai and its New Testament was initially published in Reims, France.

All of these earlier English translations would eventually be eclipsed by the publication of the most popular English translation of the Bible ever published. In the next chapter, we’ll take up the incredible story of this phenomenal translation, which, with more than 6 billion copies sold to date, is not only the best-selling translation of the Bible, but the best-selling book of all time.

1 Acts 4:12

|